The war is escalating, and both sides air operations are becoming more deadly. Ukraine’s drones recently struck Russia a hard blow. Its ‘Spiderweb’ operation destroying a significant portion of Russia’s strategic bomber fleet on 1 June. An operation quickly followed by attacks on the Kerch Bridge, that links Crimea to Russia. The bridge was damaged on 3 June by underwater drones but was quickly repaired. Although unsuccessful the attack highlighted the bridge’s vulnerability.

Russia also escalated its air attacks focussing on Ukraine’s cities and power infrastructure. On 9 June, Russia’s largest night of drone attacks was launched, 499 drones and missiles sent flying towards Ukraine’s cities. On the ground, Russia continues its offensive attacking along the length of the frontline, trying hard to make progress.

The escalating air war, Operation Spiderweb

Ukraine’s coordinated surprise attack on airbases deep inside Russian is currently a topic of discussion in mainstream media. The attack was widespread, well-planned and used drones in a new way that will concern military planners around the world because it demonstrates a new and effective asymmetric tactic.

Operation Spiderweb involved Ukraine infiltrating small, First Person View (FPV) drones into Russia concealed in shipping containers. Although the drones were launched from close to their targets they were controlled from Ukraine, using the Telegram messaging app. An effective new use of drones that is certain to be copied.

Although, Operation Spiderweb was a significant coup for Ukraine, it is only part of a wider trend. The operation demonstrates the air war is escalating, both sides increasing their focus on air power because movement on the frontline has become so difficult.

The air war’s big picture

At strategic-level, Ukraine aims to damage Russia’s military and economic infrastructure. Specifically, Ukraine targets oil infrastructure, damaging the Russia’s ability to raise export revenue to fund the war. Reuters reported in February that “The attacks have knocked out around 10% of Russian refining capacity, Reuters calculations based on traders' data showed.” The loss of refining capacity impacts on production, and therefore on Russia’s ability to fund the war.

Blunting Russian frontline combat power with air attacks deep behind the frontline is another Ukrainian objective. Deep in Russia, Ukraine’s drones and missiles strike Russian factories that produce military equipment, ammunition stores and key transport hubs. Closer to the frontline logistics facilities, command, and communications centres are all regularly attacked by Ukraine’s drones and missiles.

Russia meanwhile is also active in the air, at strategic-level Russia seeks to damage civilian morale by targeting infrastructure especially the power grid. Essentially, Russia’s aim is to make life as difficult and dangerous as possible for Ukrainian citizens. Meanwhile, on the frontline Russian aircraft make an impact using their glide bombs to blast a path through Ukraine’s defences.

My assessment is that Operation Spiderweb supports Ukraine’s overall plan in the following ways:

It contributes to degrading Russia’s air defence network.

It aims to counter Russia’s potential to use its strategic bomber force against Ukrainian cities.

Degrading Russia’s air defence network

Since the start of the war, Ukraine has worked hard to break Russia’s air defence network, and it is notable that Operation Spiderweb included attacks on two Beriev A-50 Airborne Early Warning and Control (AWAC) aircraft at Ivanovo Airbase.

AWACs aircraft are vitally important for any air campaign, these expensive aircraft fly above the battlefield using powerful radars to monitor activity. By operating at altitude, AWACs planes ‘look down’ on the battlefield and can spot low flying aircraft or missiles that ground based radars cannot see. Further, they coordinate the air battle, guiding fighter aircraft and missiles to targets, acting as tactical command hubs.

Throughout the war Ukraine has slowly attrited Russia’s fleet of A-50s. In 2023, an A-50 based in Belarus was damaged by a drone. Then in 2024 Patriot missiles claimed two more Russian A-50s. In February, Kyrylo Budanov, leader of Ukraine’s Defence Intelligence Service stated Russia has six operational A-50s. The potential loss of another two is very significant because in reinforces Ukraine’s systematic attack on Russia’s air defence radar network.

A campaign that has a long history, for example in 2023 Ukrainian forces captured the Boyko Towers, old oil wells in the Black Sea that Russia had installed early warning radars on. After the Boyko Towers were captured Ukrainian used drones, long-range missiles, and special forces raids to destroy Russia’s frontline air defence radars. This reduced ground-based radar coverage over Crimea, and southern Ukraine forcing Russian A-50 AWACs to deploy within range of Ukrainian missiles, where two were shot down in 2024.

Ukraine’s fighters generally have less sophisticated and long-ranged radars than their Russian counterparts. Further, Ukraine is only recently starting to develop a limited AWACs capability. By destroying Russia’s AWACs planes and ground-based radars Ukraine is trying to level the air battle. Depleting Russia’s air surveillance capabilities so that its drones, missiles and bombers can more easily attack Russia.

Stopping Russia’s strategic bomber force

While Ukraine is working hard to break down Russian air defences, it faces its own air defence challenge. Currently, Ukraine’s cities are protected by a range of ex-Russian and Western air-defence missiles, that are expensive and difficult to produce ensuring that they will always be in short supply. A situation exacerbated by current US policy that creates uncertainty about the long-term supply of these weapons.

Meanwhile, the Kyiv Post reports that Russian drone production has increased approximately fivefold since August 2024, from 500 per month to 2700 per month. Russia is producing more armed drones but is also making large numbers of unarmed decoys allowing it to saturate Ukraine’s air defences during attacks.

If Ukraine runs low on air-defence missiles, it faces a precarious situation because if its air defences fail Russia can deploy its strategic bomber force. A significant threat, demonstrated when these large bombers were used against Syrian cities.

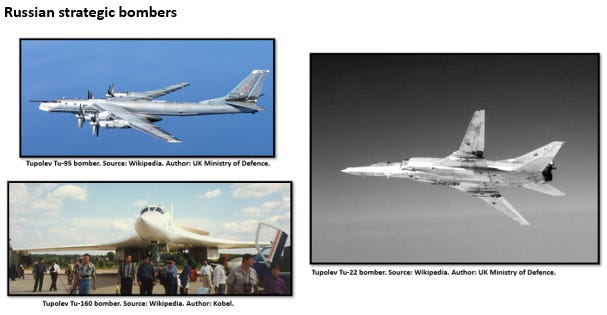

For example, a Shahed drone carries 50kg /110lbs of explosive, so if Russia’s 499 drone attack on 9 June had been 100% successful it would have delivered approximately 24,950kg / 54,890lbs of explosive. Putting this into perspective just one Tu-95 bomber can carry up-to 15,000kg / 33,000lbs of bombs. The newer and more sophisticated Tu -22 bomber can carry up-to 24,000 kg / 53,000 lb, and the even more modern and capable Tu-160 bomber can carry up-to 45,000 kg / 99,208 lb.

The destructive capacity of these machines is considerable, for example in Syria, Russian raids sometimes involved six Tu-22 aircraft with a combined war load of up-to 140,000 kgs / 318,000lbs of bombs. Delivering the same amount of explosive would require 2,800 Shahed drones. Although, very rough this analysis demonstrates the destructive potential of Russia’s strategic bomber force.

Both Tu-22 and Tu-160 bombers helped bomb cities in Syria. Currently Ukraine’s air defence is strong enough to keep these aircraft safely in Russian. However, if Ukraine’s air defences start to fail, it may open a window of opportunity for these aircraft used.

Operation Spiderweb indicates that Ukraine is concerned about this situation, and is taking steps to mitigate risk by targeting these aircraft. Likewise, the attack damaged AWACs aircraft that can support bombing missions because without airborne surveillance, bombers can be engaged more effectively by Ukrainian fighter aircraft. Less Russian AWACs capability means Ukrainian fighters can more effectively supplement increasingly scare missiles.

Further, Operation Spiderweb forces Russia to disperse its bomber fleet making it harder to support them logistically and drawing more air defence radars, missiles and artillery away from the frontline.

The situation on the ground

At operational-level, the campaign continues to evolve into a large Russian ‘turning movement.’ Russia’s main effort remains Kostyantynivka but its forces continue to create a dilemma by threatening Sumy. Most reports place 60-70,000 Russian soldiers in the Sumy area. A force that is unlikely to be large enough to capture a city of approximately 250,000 people.

However, if a Russian force can fight to within range of artillery and drones, the people of Sumy will be in great danger. Currently, far to the south-west in Kherson there are reports of constant artillery shelling, and of Russian forces using drones to terrorise local civilians. Al Jazeera reported in January that “Last summer, the Russian army appeared to adopt a new tactic. They started flying dozens of drones in south Ukraine to follow cars and people in a video game-like chase. They have dropped explosives on civilian targets, wreaking havoc, according to Ukrainian officials.” It is possible that if Russian forces get within FPV and artillery range, Sumy’s population could suffer the same treatment.

Therefore, there is good reason for Ukraine to prevent Russia from capturing Sumy. A threat Russia is exploiting to draw Ukrainian soldiers away from Kostyantynivka.

Russian forces are blocking the H-32 highway that links Pokrovsk and Kostyantynivka. And Russia’s main effort remains capturing Kostyantynivka, and its most direct line of advance is via Toretsk. An area that is currently experiencing heavy fighting, and where elite Russian drone units have been redeployed. The movement of these units is a modern ‘combat indicator’ of Russian main effort and we need to watch this area closely for any sign that Ukraine is losing ground.

Further south, Russia recently advanced crossing the border of the Dnipropetrovsk region between the villages of Horikhove and Novopavlivka. Although this advance is of little tactical significance it was well-reported because it is the first time that Russian forces have crossed the Dnipropetrovsk border. This attack is not likely to be noteworthy at tactical or operational-level, because the ground taken is of limited value. Instead, this advance is likely to be a minor attack supporting the main effort further north.

A more worrying Russian area of interest is further north, where Russian soldiers have consolidated a position on the west bank of the Oskil River near Zapadne village. The river is an important defensive barrier between Russian held Luhansk region, and the important Kharkiv region. The river could also be used to secure the flank of an advance south towards Kupyansk. Russia’s advance in this area might be slow but is consistent.

Conclusion

Russia continues to demonstrate that it does not want peace, presenting an uncompromising set of demands in Istanbul early last week. If Ukraine had accepted Russia’s demands including; demobilising its military, neutrality and not joining NATO, it would have amounted to a conditional surrender.

Instead, Ukraine’s response was to strike back - hard. Operation Spiderweb is a pragmatic response targeting two dangerous Russian capabilities, its AWACs aircraft and its strategic bomber force. An operation indicating Ukraine has concerns about Russia’s strategic bomber force. A force that has proven highly destructive in Syria, and that Ukraine certainly does not want used against its cities.

Operation Spiderweb was successful, and will impact for some time as Russia tries to find ways to secure its aircraft from similar attacks. However, it has not entirely mitigated the threat posed by Russia’s strategic bomber force, reminding the world how important it is to maintain continuity of supply for Ukraine’s air defence weapons.

Russia’s recent advances on the ground are being reported and discussed in the media; but my advice is to remember that in this war, the important ground is the villages and towns. Urban areas that can be defended, places like Pokrovsk, Chasiv Yar and Kostyantynivka, that Russia has been throwing its soldiers against without success for the last year.

Instead, the most important recent activity is Russia’s threat against Sumy. Russia does not have sufficient soldiers to capture this large city, so probably intends to simply attack it with artillery and drones. A threat Ukraine must take seriously, and whether Ukraine has the resources to simultaneously defend in Donetsk and Sumy is the next question.

Thanks Ben. As usual an excellent summary and advisory of happenings; from both a strategic and tactical POV. I hadn't been aware that the hugely successful drone attack on Russian airbases had been controlled from Ukraine!

Thanks for your support Peter. I'm glad you like reading my work,