Breaking through the modern battlefield’s defensive ‘kill web’

Recapturing offensive manoeuvre requires Western armies to find solutions to breaking through a defender's ‘kill web,’ and to achieve this goal several tactical assumptions may need to be reversed.

Victory on land, is the art of using operational, and ‘major tactical’ level manoeuvre to concentrate enough force to inflict decisive defeats on an enemy force. Most often this is achieved through offensive manoeuvre, attacking the enemy.

In Ukraine new technologies caused defensive tactics to evolve, making large-scale, decisive manoeuvre difficult. But does this mean offensive manoeuvre impossible?

This article argues that offensive manoeuvre is still possible, but requires planners and commanders to reverse several key assumptions about force structure and ground.

New technology means defence is currently pre-eminent creating a ‘frozen battlefield’

Three years of war in Ukraine has stimulated discussion about the future of land war. Mostly, at the tactical-level as soldiers and commentators struggle to come terms with a range of technological innovations that favour the defence, specifically:

Greater ‘transparency.’ The omnipresence of drones, and other surveillance assets provides vastly better, and more timely situational awareness.

Democratisation of precision-strike. The ability to hit a target instantly and accurately is now available at all levels of combat. From the individual solider operating an FPV drone or loitering munition, through to long-range missile strikes hitting targets far behind the enemy’s frontline.

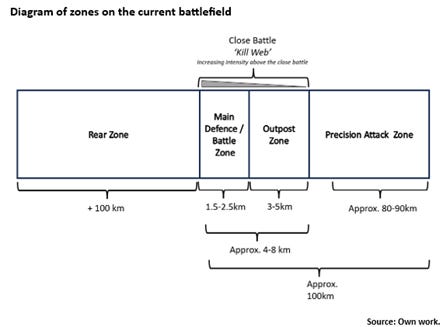

The impact of these technological innovations is profound, allowing both sides to impose area-denial on large parts of the frontline. Coining an American term, transparency and immediate strike throws a ‘kill web’ over the frontline. ‘Freezing’ large-scale offensive manoeuvre within its boundaries

The kill web currently limits large-scale manoeuvre and ‘fixes’ an attacking force in place, by dispersing it into small groups to survive. A situation that negates traditional concepts of combined arms attack that rely on concentration of force, in open terrain.

But this situation is not new

The current situation in Ukraine is reminiscent of World War One, a war in which new technology like barbed wire, machine guns and coordinated artillery fire achieved the same effect. After its initial successful 1914 offensive, Germany realised that to hold the ground it had captured, it needed to develop sophisticated system of defence. The doctrine of ‘Abwehrschlacht,’ or “defensive battle,” emerged. This doctrine created an early 20th century kill web, in which new technology made fires response quicker, more accurate, and more lethal multiplying the power of the defence.

Abwehrschlacht was an efficient system of defence in depth, that replaced trench lines with strong points distributed across a series of defensive zones. The first or ‘outpost zone,’ was lightly defended and aimed to disrupt enemy advances providing time for resources further back to mass against the attacker’s axes of advance. This zone could also ‘shape’ the enemy because like water, an advance will tend to follow the easiest route. So by giving or holding ground, the outpost zone could direct the enemy into more heavily defended areas.

The second or ‘battle zone,’ prioritised defeating the enemy and was where the main defensive battle was fought. The outpost zone provided warning. So soldiers and artillery could be massed on the enemy’s lines of advance.

The third or ‘rear zone ‘provided a secure area from which to stage counter-attacks, and fall-back positions to prevent an enemy break throughs. This system relied on new technologies like machine guns, barbed wire and long-range artillery fire within the Abwehrschlacht, and created ‘area-denial.’

Using new, contemporary technology German forces effectively froze the frontline, preventing large-scale operational manoeuvre until late in the war when new tactics and technologies broke their kill web. A similar pattern has emerged in Ukraine, and now both sides drones and precision-strike weapons create area-denial zones along the frontline.

The frozen battlefield’s key differences, what is new

In Ukraine, both side’s defensive schemes are evolving in a similar pattern to the Abwehrschlacht, but with two key differences:

The close battle’s ‘kill web’ is tighter. In World War One, machine guns and indirect fire coordinated by radio and telephones combined to create a ‘kill web’ over the close battle. A tactical innovation subsequently defeated by new combined arms tactics. Now, ubiquitous surveillance and precision-guided weapons combine with existing weapon systems to create an even denser defensive fire zone that can defeat current combined arms tactics in the ‘close battle.’

A new precision-attack zone. New longer-range surveillance technology, drones and precision-guided missile have created a new zone, that I have termed the ‘Precision Attack Zone.’

Greater depth and increased surveillance of it make the attacker’s task more difficult because long-range missiles and drones can destroy an attacker’s reserves as they concentrate. Further, an attacker now faces indirect attack tens of kilometres in their own depth and that fire is often highly accurate. The defender’s ability to attack in depth also reduces the attacker’s ability to mass artillery and build fire supremacy.

Russia’s tactical evolution

The Russian Battalion Tactical Groups that swarmed across Ukraine in 2022 are gone, replaced by Storm Z tactics focussed on section-level organisations. Russia evolving a new tactical system designed to defeat Ukrainian area-denial - Storm Z tactics. And, by employing this tactical system Russia is achieving slow but consistent large-scale manoeuvre.

Storm Z, sometimes called ‘meat waves’ were pioneered by the Wagner Group, and use dispersion and small infantry units to reduce the effectiveness of Ukrainian area-denial. A small unit is harder to locate, and is less likely to be engaged. The smaller a target, the less likely a defender is to unmask their artillery or to use other limited resources like drones to attack it. Therefore, by using many small units on a wide frontage Russia forces Ukraine to husband indirect fire resources limiting their massed effect.

Dispersion of force, limits the ability to concentrate force, generally mitigating against large-scale manoeuvre. And, without large-scale manoeuvre how can a force inflict a decisive blow on its enemy? Russia has solved this problem by sacrificing manpower to inflict decision slowly. Inexorably, grinding away at enemy defences like sandpaper on wood.

Although costly in human lives, Storm Z tactics backed by glide bombs and drones work, so may be copied and improved by Russia’s partners. For example, a Chinese, North Korean or Iranian force unconcerned about casualties and using similar tactics would be difficult to defeat.

The element missing from the Russian system is exploitation of a defeat. At Bakhmut, Avdiivka and Vuledhar Russian forces captured significant towns that could have provided a firm base for further exploitation but did not pursue the defeated enemy.

Why?

My assessment is that Russia simply lacks the armoured mobility to pursue because it has lost to many tanks, armoured fighting vehicles and trucks. But imagine if their tactical success was followed by a rapid exploitation, driving deep into Ukraine’s rear areas attacking logistics infra-structure, command centres or digital infrastructure. An operationally significant defeat could be inflicted, and this scenario is worth considering especially in light of the potential for these tactics to be copied and improved by more capable militaries.

What about Ukraine?

The largest operational-level manoeuvre since 2022 was the Kursk Offensive. A successful tactical advance that appears to have successfully influenced the operational-level campaign, diverting Russian resources away from their main effort in Donetsk.

However, a salient feature of this operation is that it was conducted using conventional tactics. Mechanised combined arms brigades manoeuvring in traditional ‘movement corridors.’ The Ukrainian force maximising surprise, and appearing to generate local EW superiority that temporarily defeated Russia’s local kill web.

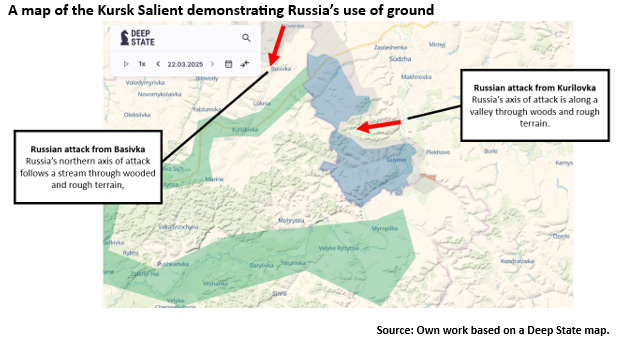

The salient created was eventually closed by Russian forces using Storm Z tactics, area-denial and massed indirect fire. The tactical system can be described as follows;

Area-denial uses surveillance, artillery and drones to ‘fix’ the enemy, while depth fire slows down reinforcement.

Massed indirect fire including glide bombs, massed artillery and missiles attrit the enemy.

The weakened enemy is slowly reduced using Storm Z infantry tactics, making use of complex terrain to manoeuvre inside Ukraine’s area-denial ‘bubble.’

Ukraine’s salient was slowly reduced, and Russian tactics appeared to be effective, especially when US intelligence information was restricted making targeting in the ‘Precision Strike Zone’ more difficult.

A situation that indicates a manpower advantage can defeat even modern area-denial in the ‘close battle.’ Additionally, a feature of Russia’s small group tactics is the use of complex terrain to limit decisive indirect fire engagement, a useful lesson for tacticians.

Another potential lesson is that any attacker needs to protect their depth, Ukraine’s defensive system worked best when Russia’s front-line was dis-located from its logistics support. Further, control of the enemy’s rear (in the Precision Strike Zone) is a mitigation against a potential follow-on force undertaking exploitation of a ‘break in.’

Thinking about Western armies

Modern Western armies are razor sharp, well-trained weapons honed with lessons from large conventional conflicts like the 1993 and 2003 Gulf Wars, and from 20 years of fighting insurgencies during the Global War on Terror (GWOT). The lessons of the GWOT however are most recent, and these lessons can be contrary to the way war-fighting is evolving in Ukraine.

A noteworthy evolution in Western armies is the rise in the influence of ‘special forces’ (SF) leaders. SF are specialists in small wars and combating insurgents, so rose to new level of prominence during the GWOT and now fill important leadership positions throughout Western militaries. Influencing training and procurement, changing the force structures and capabilities of Western militaries away from conventional operations towards asymmetric operations.

Some examples of this trend include Western militaries reliance on digital communications and high specification equipment. A trend driven by the asymmetry of the GWOT in which vastly larger and more sophisticated militaries could over-match their opponents. For instance, in Afghanistan all Western militaries operated supported by a highly effective logistic chain, complete with large and very secure forward bases that could easily maintain sophisticated equipment. A luxurious situation compared to the near-peer war being fought in Ukraine.

In January 2025, the German military attaché to Ukraine conducted a lecture in Delitzsch, and transcripts reveal a range of issues with his nation’s equipment, that can be summarised as follows:

Modern German equipment like the PzH 2000 self-propelled gun, and Leopard 2A6 tanks is very effective but is sophisticated and difficult to maintain or repair.

Older, Cold War weapon systems like the Leopard 1A5, Marder and Gepard are proving their worth because as well as being effective they are easy to maintain.

German supplied air-defence missiles are excellent but expensive, and difficult to maintain.

This information concurs with criticisms of UK and US Challenger and Abrams tanks that although lethal, are a maintenance burden. The success of the one of the least sophisticated pieces of Western equipment provided to Ukraine, Australia’s Bushmaster armoured truck, provides further evidence that numbers and reliability are more important than sophistication in conventional war.

Modern Western militaries also rely heavily on digital networks for communication. During the GWOT Western militaries developed very high-quality communications, video feeds and battle-tracking systems that greatly enhanced their effectiveness. However, a near-peer opponent is likely to be able to jam, spoof or generally interfere with these capabilities in ways that Iraqi insurgents, or the Taliban could not.

Leaders of Western militaries need to develop a tactical system that allows for operationally significant manoeuvre in the face of the following new considerations:

Conventional war is no longer an anachronism, so larger less sophisticated forces need to be developed.

The battlefield is highly ‘transparent.’

Large areas can be denied to significant concentrations of force.

Evidence from Ukraine indicates Russia is already developing a tactical system and demonstrating the capacity to win a conventional war. This system may be replicated by other more capable enemies like China, and modern Western armies may not currently be able to match forces fighting in this manner. China is already investing heavily in area-denial and combining their sophisticated existing precision-guided weapons with Storm Z tactics could produce a dangerous enemy.

On today’s battlefield the general’s role is becoming harder because generating the mass required for rapid, decisive manoeuvre is difficult since any concentration of force is hard to hide. Further, concentration of force into area-denial is suicidal, as drones and long-range artillery, aircraft and missiles concentrate their activities against the force.

This means that how generals and their staffs think needs to change, rapidly.

In Organic Design for Command and Control, strategist John Boyd challenged conventional concepts of command and control. He argued that an organisation needs to be externally focussed, continuously ‘orientating’ itself to external stimuli, and developing a culture of constant evolution based on ‘appreciating’ the impact of those stimuli.

Ukraine is providing plenty of stimulus and Western militaries need to radically challenge, and even reverse several tactical assumptions.

Reversing key tactical assumptions

Re-considering ground - good ground is now bad ground

The first impact of ‘transparency’ and widespread ‘precision-strike’ relates to the relationship between soldiers and the ground. Open country is dangerous on the current battlefield, constantly survieled by drones and satellites, so any movement is likely to attract indirect fire. Therefore, soldiers look for alternative routes that conceal their movement, and the cost of concealment is slower movement.

In Ukraine, we have seen an organic response, frontline units independently appreciating the change and operating differently while command policy catches up.

Advances are made through close country, rough terrain and urban areas. The map below from 22 March 2025, shows how Russia advanced into and around the Kursk Salient. Instead of using open-country to conduct large-scale movement at speed, Russian forces advanced where there is cover sacrificing speed for concealment.

This change is significant, especially for staff officers, the planners that enable a commander’s vision to be implemented. Where the current generation of staff officers see a ‘movement corridor’ or a ‘main supply route’ in open ground, combatants in Ukraine see destruction from to sky.

Leadership is the first challenge because coordinating widely dispersed forces moving through complex terrain is difficult. A task that becomes more complex as electronic warfare develops and everything from GPS to digital data transmission and radios can be jammed or spoofed. Perhaps we will see return to land lines becoming the primary ‘means’ for communication between units.

Auftragstaktik or ‘mission command’ doctrine is the traditional response to leading forces operating in small dispersed groups. However, Western armies currently suffer because of their universal ability to communicate during peacetime manoeuvres and in asymmetric conflict. Small-scale and SF operations often being run tactically from force headquarters far removed from the battlefield, with expectations for guaranteed fire support and senior leaders immediately able to provide guidance. And, whether auftragstaktik can be practised in by Western armies needs to be tested, if they are to make full use of the ground to conceal movement.

Essentially, can Western militaries operate effectively without guaranteed digital communications, and with their ‘Blue Force’ operational trackers switched off?

Supplying and leading forces dispersed in complex terrain is a slow and time-consuming task. The impact of these factors is to further slow down manoeuvre. Finding ways to supply small, widely dispersed units, or to evacuate the injured in complex terrain is another challenge. Recently, are reports and footage of Russian forces using pack animals to supply the frontline. Perhaps, there is a method to this madness because a mule can move through any terrain a man can providing option to resupply small units in complex terrain. However, it takes a lot of mules to supply a brigade or a division.

Reassessing force composition in the attack

At force level, a change in the composition of an attack force is required. Reversing current assumptions about force structure. Instead of penetration being achieved using an armour heavy combined arms force every brigade, division or corps needs to reverse the conventional tactical model and develop a self-supporting light force element able to ‘break in’ backed by forces for exploitation and holding the ground that was taken.

The structure of these forces can be seen as a reversal of conventional tactical systems.

The ‘break in’ force

This force is a swarm of light, combined arms teams (i.e. EW, ground and air drones, mortars, light artillery and air-defence) that are self-supporting and can operate independently for days, in digital silence using auftragstaktik. Moving self-sufficiently without resupply, or new orders, and operating under the enemy’s area-denial zone. A force able to move and fight in complex terrain like woods, urban areas and broken country. Its objective is to ‘break in’ by compromising the defensive kill web’s ‘sensors.’ Human observers, EW monitoring stations, Ground Surveillance Radars, Remote Ground Sensors, and forward drone operating teams.

A force designed to ‘pick out’ the enemy’s ‘eyes’ that operates in small teams unlikely to attract the attention of massed drones or indirect fire within the kill web. This force’s role is to disrupt the ‘sensors.’

Another of the swarm’s roles is establishing a protective EW bubble, and physical infrastructure for the digital communications net that will support follow on forces. For example, before the Kursk Offensive, Ukraine closely monitored Russian drone activities identifying frequencies, and then used a range of jamming devices to shut them down. Russian radio communications were also jammed. Ukrainian forces pre-positioned jamming assets on the border, and brought tactical EW assets forwards with lead units. Some sources report that Ukrainian drones were used to position jamming devices ahead of the advance, although this has not been confirmed.

The ‘break in’ force’s operations should be coordinated with other arms. Its operations supported by air attacks, like Russia’s glide bombing tactics. A deliberate and planned air attack would precede then support infiltration of the ‘break in’ force. Artillery, drones and long-range direct fire would also support the force, alongside supporting attacks to draw away or confuse defending forces.

And, it should be clear that the role of this force is not fighting into large defensive positions, but rather to locate, envelope, and open the way for heavier forces.

In Western armies I see the opportunity to evolve forces of well-trained infantry soldiers organised like the USMC Littoral Combat Regiment, but with a stronger infantry component, for this task.

An exploitation force, the sudden application of mass

Ukraine’s Kursk Offensive demonstrates that comprehensive area-denial will always be limited along the frontline, only priority areas being densely covered. Further, it is safe to surmise that in depth there is less likelihood of comprehensive area-denial.

Thus far in Ukraine, neither side has been able to break through the enemy’s frontline area-denial, and rampage through the less protected rear areas. This phase requires a different type of force, most likely based on wheeled armoured infantry and held ready far behind the ‘break in’ force. Neither Russia or Ukraine appears to have been able to generate a force like this, probably indicating that both sides lack the resources to generate reserves in depth.

Modern wheeled armoured vehicles can cover hundreds of kilometres overnight, allowing them to be held in multiple locations far behind the frontline, preferably outside the Precision Strike Zone. A distance the seems achievable with modern wheeled armoured fighting vehicles, that are both fast and reliable.

The exploitation force can swarm forward as the enemy’s area-denial is compromised. This force would be self-sufficient and able to operate independently for days at time. Like the ‘break in force,’ the ‘exploitation force’s’ role should be focussed on envelopment, rather than reduction of enemy positions. This force’s raison d’etre is creating momentum, forcing the enemy to step back by rapidly swamping their Battle Zone with combat power.

This force exists to expand the breech created by the ‘break in’ force, and does this by bypassing large positions. Stopping to reduce a large enemy position, slows momentum and provides targets for drone, missile and artillery attacks. However, there will be times that a defensive position cannot be bypassed and this force needs to be prepared, well-supported by other arms and strong enough to quickly overwhelm a target. The ‘break in’ force providing intelligence, so that attacks are well-planned, and executed with precision.

A general’s sense of space will need to evolve because their ‘break in’ force may probe on several vectors but be supported by the same ‘exploitation’ force. This requires the commander to be thinking in large and expansive terms and for their delegated authority to cover large areas of the rear. Likewise, staff officers will need to plan and control large fast movements to get the ‘exploitation’ force to where it is needed, pulled forwards by a successful ‘break in’ force penetration of the kill web.

The ‘exploitation force’ is equipped with more EW capabilities, air defence, and drones. The aim being to establish electro-magnetic and air defence dominance of the captured area as quickly and completely as possible. Further, the force’s deployment will need to be covered from air and precision attack. The force’s speed provides protection, so it must operate wither a wider air defence bubble.

Thinking laterally, an ‘exploitation’ force could even achieve surprise by using air-mobility or sea mobility. If an air defence bubble can be created, even for a short time, tactical transports or large helicopters could bring forward reinforcements from great distances. The Rhodesian Bush War provides examples of air transport being used to facilitate sudden, surprising manoeuvres. Modern lightweight vehicles provide airmobile forces with mobility, heavy weapons, and carry forward EW resources. Likewise, in littoral operations the ‘exploration’ force might be seaborne, sitting ready many kilometres away from its point of impact.

Using echelons, to consolidate

Exploitation requires the ground captured is held, and on the modern battlefield that means quickly establishing friendly force area-denial. Any offensive needs an echelon consisting of the following:

Reinforcements, to hold captured ground.

Logistics assets to re-supply and re-constitute the ‘break in’ and the ‘exploitation’ force.

Digital infra-structure to quickly establish local digital communications.

Artillery, armour and drones to support securing the ground.

Air-defence, larger more sophisticated air-defence assets.

Reduction of the enemy’s now isolated outposts is a role of ‘echelon’ forces, and this group has heavy artillery, armour and engineering assets that can be concentrated and operate safely within the ground and electro-magnetic space dominated by the ‘exploitation force.’ Additionally, these assets would be used to build a new defensive perimeter within this space.

Like an ‘exploitation force,’ the operation’s ‘echelon’ would be held to the rear but closer behind. Heavy equipment like tanks, artillery and heavy engineering assets are hard to move, and are likely to be part of the attacker’s existing defensive line. Essentially, this force’s heavy equipment would bulge forwards into the ground captured by the ‘exploitation force.’

Conclusion

Ukraine is changing tactical assumptions, mostly we discuss these changes at the minor tactical level. But this war demonstrates that we need to be challenging assumptions at all levels of tactical operations.

Specifically, accepting that any attacking force must break through the defender’s kill web of integrated fires. Artillery, drones and direct fire weapons working together within a seamless integrated ‘sensor – shooter’ web, that allows accurate, instant and deadly fire. Freezing the battlefield by denying the attacker the ability to mass force in the close battle.

Breaking through the kill web is the key conundrum of modern minor tactics, and solving the problem requires modern tacticians to reverse current several assumptions about ground and force composition.

Thank you for the great article, it really got me thinking about modern warfare., In the long run history usually favors offence over defense but the current state of drones and precision weapons favor the defense. What we are also seeing if the advantage of mass produced cheap weapons over expensive sophisticated weapons. If a ground support F16 or A10 warthog can be killed with a small drone, the role of combat support aircraft is obsolete.

Maybe its time to re-think why one wants to gain land territory in the first place? Perhaps one wins a war by destroying the enemy's warfighting economy and forget about boots on the ground.

Minefields are inconvenient, but fairly easy to clear with the right engineering asset. if you haven’t ever seen a fuel-air explosive detonated before, you just need a vapourized fuel distributed over a suspected mine field, and an igniter to set it off. The resulting pressure wave will usually take out a high percentage of mines. Of course you have also signalled in a very vivid way exactly where you are going to move, but that’s the risk in a minefield breaching operation.

This is, as Mr. Morgan stated, all part of pulling apart the enemy’s ‘kill web’.

The Ukrainians will most likely not need to go to such lengths: operations will need to move along multiple routes, where the recon elements have identified mines and IEDs intended to stop a column in a kill zone, and will have either disabled or had artillery or drone assets use HE rounds to clear them. We might even see the return of some of Hobart’s ‘Funnies’ to speed things along.

I learned the older defence in depth methods at BIOTC back in the 80’s, and while the extra dimensions seem overwhelming, it makes sense that the fields are stretched almost 100km on each side. The defensive nature is like a WWI trench - no man’s land - trench defences but with artillery that can drop CBMs, drones with mortar rounds, and EW to blind the enemy.

Speed will remain essential in any offensive operations, and while tactical surprise will be very hard to achieve, deception and mis-direction will be stock and trade, right down to the Other Ranks. Having the enemy waste rounds on dummy targets will be more and more important. Ghost units will make it harder to sort through which one to target or know where the real unit is.

I look forward to reading the rest of this stack to see what other veins of gold show up.